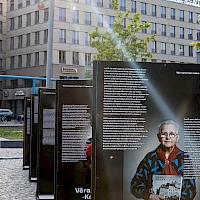

She is one of the descendants of the emigrants who came to Czechoslovakia from the former Russian Empire at the beginning of the 20th century. Her father Jevgenij Feofilovič Djukov, an officer in the White Army, studied medicine in Prague thanks to the so-called Russian Aid of the young Czechoslovak state. After his studies he set up a practice in Smíchov and met Erika Kaprasová, who worked as a midwife's assistant in Radlice. After their marriage they worked together and soon Eugenie was born and a year later her brother Vladimír. After the war, the father barely escaped being taken into Soviet captivity.

Eugenie trained as a nurse and after two years in the hospital under Laurenziberg in Prague she was able to start her medical studies at Charles University. This was during the loosening atmosphere of the 1960s, which ended with the invasion of the Soviet Army in August 1968. Eugenie joined the protests and travelled with her boyfriend Jiří to Yugoslavia, where they got married in 1969 at the embassy in Zagreb. They decided to return to Prague, although Eugenie was not allowed to continue her studies. On the recommendation of MUDr. František Kriegel she found a job as a laboratory assistant and later as a specialist assistant in the Institute of Clinical and Experimental Surgery on the premises of the Thomayer Hospital. Later it became the Institute of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, where Eugenie still works today.

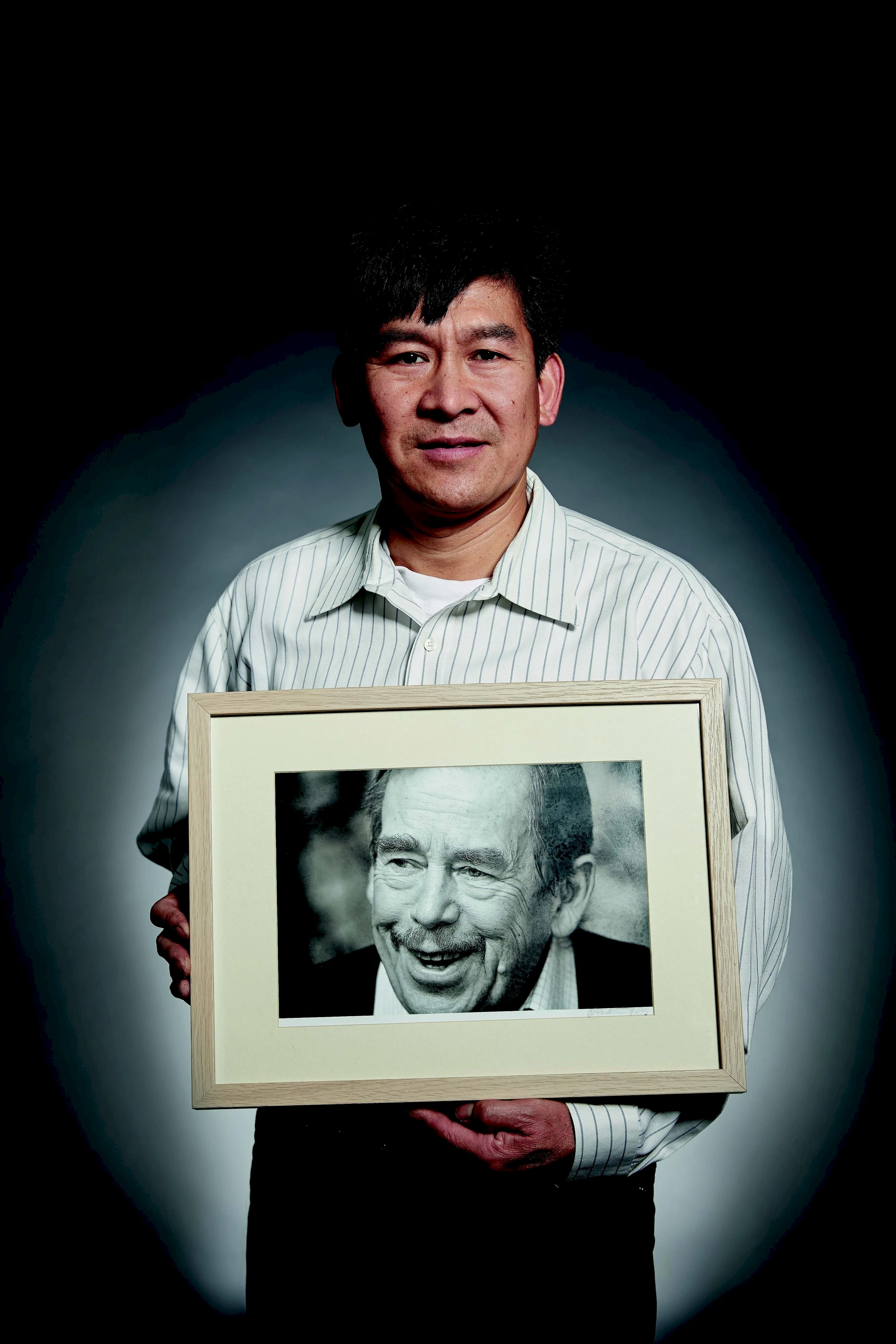

For her, the photos of President Masaryk and her father symbolise the Czech Republic, because she is grateful to both of them for her living here. "I am grateful to President Masaryk for the fact that, thanks to his Russian aid campaign, Czechoslovakia welcomed emigrants from the Russian Empire who were fleeing from Bolshevism. My father was one of them."

The exhibition was supported with EU funds from the Small Projects Fund in the Euroregion Elbe/Labe.

The exhibition was supported with EU funds from the Small Projects Fund in the Euroregion Elbe/Labe.